A Bengali without her Begun Bhaja (fried brinjal) is almost like Bengal without Tagore. Which is why the name given to this vegetable by Bengalis has always intrigued me. Pronounced, ‘Begoon’, literally translated it means ‘sans any guna or good properties’. It makes me also wonder whether the Hindi word for brinjal, ‘baingan’, could have been derived from ‘bina gun’ or devoid of good properties?

Growing up I rejected it, finding numerous reasons not to like it — the mushiness, the sliminess and last but not the least, believing strongly that our forefathers knew what they were talking about when they named this vegetable or fruit, call it what you may, such. However, soon enough I realised however much I loved to hate it, I couldn’t escape it. It was a key player in the finest of Bengali vegetarian dishes, not to mention the cuisine of the rest of India. Moreover, there were speciality dishes to complement the various sizes, shapes, colours and textures it came in – the royal purple, pale green and pristine white, the first lending its name for the colour purple in Bengali and the last responsible for it also being known as eggplant.

Today there are about 20 varieties of brinjals, many of them seedless.

Today there are about 20 varieties of brinjals, many of them seedless.

It was then that I came across some fascinating research on the antiquity and socio-cultural evolution of this plant by various scholars in Asian agri-history journals, among other scientific research papers. The brinjal, it seems, was India’s gift to the world, originally native to the drier regions of Bengal and south of India. Domesticated from a rather prickly wild plant with round green fruit and seeds that had a bitter flavour, centuries of evolving farming techniques altered the size and shape, trimmed the plant down to lesser or no prickles, and changed the flavour of the flesh and skin. Today there are about 20 varieties of brinjal, many of them seedless.

Philological studies indicate that it existed in India during the prehistoric and pre-Sanskrit civilisations. One name for the brinjal – Vartaku – considered a pre-Sanskrit word, is derived from an ancient Indian language spoken by the Mundas or Austrics, one of the oldest inhabitants of India. From the subcontinent it moved to West Asia and Europe. It probably grew in China as well but was not considered fit for consumption till much later times. In Europe it was more of an ornamental plant with its colourful pendulous fruit.

We find mention of this fruit in the Ramayana. According to renowned food historian KT Achaya, the 16th century treatise Krishnamangala, set in the times of the Mahabharata, includes brinjal in the list of items cooked by the gopis of Vrindavan at Lord Krishna’s request. It was probably from Nabadwip, in Bengal, that the brinjal travelled down south to Udupi in Karnataka, famous for its unique Mattu Gulla variety of brinjal, carried by the 16th century saint Vadiraja, author of the first known Indian travelogue in Sanskrit, Tirtha Prabandha. According to Ramesh V Bhat and S Vasanthi of the Centre for Science, Society and Culture and ICMR, respectively, “It is interesting to note that the green brinjal, round in shape with spines and resembling Mattu Gulla (though not similar in taste), is available in the Kolkata markets even today”.

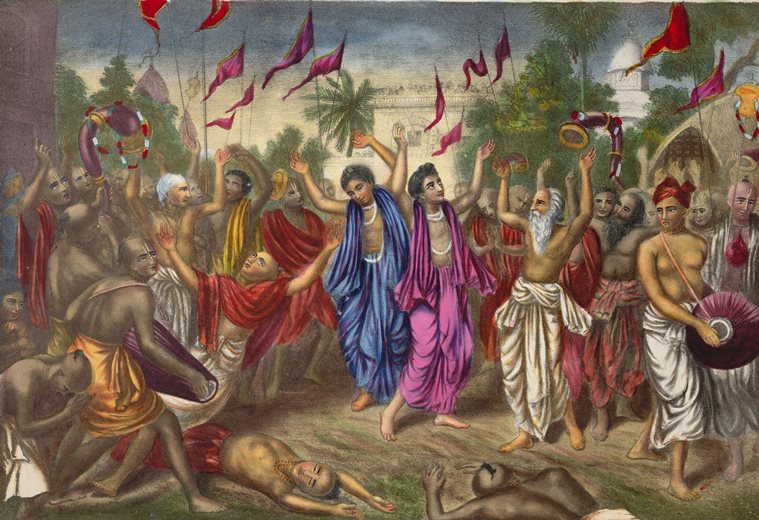

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who founded Gaudiya Vaishnavism, and Nityananda, are shown performing a ‘kirtan’ in the streets of Nabadwip, Bengal. Bengali vegetarianism is heavily influenced by Vaishnavism. Photograph courtesy The British Library

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who founded Gaudiya Vaishnavism, and Nityananda, are shown performing a ‘kirtan’ in the streets of Nabadwip, Bengal. Bengali vegetarianism is heavily influenced by Vaishnavism. Photograph courtesy The British Library

If such was the popularity of the brinjal from the ancient through medieval times, why does literature throw up evidence that it was also shunned, perhaps leading to the Bengali nomenclature Begoon? Bengali vegetarianism being heavily influenced by Vaishnavism, the first reason could be that brinjal mixed with bitter neem leaves was said to be a favourite with Lord Shiva, who is of tamasik nature while Vishnu is sattvik. Hence, brinjal was considered inferior, much like mustard oil is used to cook Lord Shiva’s food, while pure ghee is Vishnu’s choice. As one food writer put it succinctly: “Ordering melanzane alla parmigiana at a South Philly restaurant may sound elegant to our ears, but the Italian word for eggplant is thought to be rooted in the Latin words mala insana, or ‘apple of insanity’.” Italians weren’t the only ones wary of the vegetable’s possible poisonous traits. The English sometimes called eggplants ‘mad apples’.

The real reason probably was health-oriented, markedly stronger while the fruit was in its initial wild form. The brinjal belongs to the night-shade family of plants, which produce alkaloids that can trigger toxic and psychotropic effects. Heightened toxicity can lead to allergies like itching of skin and throat, hives, wheezing, etc. The psychotropic effects can be mood altering because the seeds of the fruit contain some amount of nicotine, more than any edible plant. However, as scientists have pointed out, the amount of nicotine in the brinjal or any other plant is negligible compared to passive smoking and brinjal-induced side effects are rare.

Centuries of studied domestication of the plant has led to the fruit now being recognised as a dietary solution to Type II Diabetes in its early stages because of its high fibre and low soluble carbohydrate content. It is also for the same reasons that boiled brinjals make for effective slimming food as it does in addressing cholesterol issues. The fruit is rich in Vitamins A and B.

There are some interesting references to the indigenous technology used to produce superior varieties of this fruit in ancient Indian literature. The Vrikshyayurveda is one such ancient text that records the various methods by which superior strains of the brinjal could be grown. For instance, brinjal seeds fertilised and nourished with the bone marrow of female boar would yield a larger and seedless variety. While it may sound like old wives’ tales, the importance of bone marrow fluids is recognised by stem cell researchers today. In yet another section of the text it is stated rather curiously: “A small hole should be bored in a tender ashgourd and seed of a neem tree, profusely smeared with honey and melted butter, should be dropped in through the hole. After the gourd is fully ripe, the seed should be carefully extracted and sown. It then produces a plant which produces ample wealth in the form of brinjals of huge size.” Well, I wouldn’t put anything past our ancient sages when it came to bio-engineering.

Along with such farming techniques, ancient and medieval texts propound on how to cook the brinjal as well. Nowadays, cooking brinjal with meats is not a norm in India. However, we find mention of dishes like brinjal cooked with mutton or jackal meat in the monumental 12th century tome Manasollassa. There are other descriptions in epic medieval literature of brinjal with wild duck or unusual dishes such as something called Kavachandi made with finely chopped mutton, flavoured with powdered spices and grains and shaping them into tiny balls, called vataka, the size of jujube fruit and then deep fried. The vatakas, the forerunner of the modern-day koftas, were then put into a spicy curry along with diced brinjal, radish, onions and sprouted green gram paste.

It is said that the brinjal travelled to Udupi from Nabadwip, in Bengal, carried by the 16th century saint Vadiraja. Photograph by Ravi Shankar Guntur/Flickr

It is said that the brinjal travelled to Udupi from Nabadwip, in Bengal, carried by the 16th century saint Vadiraja. Photograph by Ravi Shankar Guntur/Flickr

There are vivid descriptions in other medieval texts as well of cooking brinjals with ghee, salt, methi and cream or what now appears to be the age-old bharta by roasting on coals with ghee. A text describing royal feasts describes a grand bharta made with ghee-roasted and mashed brinjal, coconut, curry leaves and cardamom and then flavoured with lime juice and camphor.

Last, but not the least, this once much-maligned fruit or vegetable, whatever you call it, has crept into folklore as well. The idol of Lord Krishna at a temple in Udupi is still offered brinjals on festive days as per the Lord’s own request four centuries ago. Eastward, in Bengal, film maker Satyajit Ray’s grandfather, satirist, master of nonsense verse and children’s literature Upendrakishore Roychowdhury, in his Tuntuni ar Biraler Katha (The Tale of the Tailorbird and the Cat) narrates the story of a tailorbird guarding her nest of fledglings from the evil cat. The nest is tucked away in the leaves of a brinjal plant. As with all such stories, Tuntuni manages to hoodwink the cat, who receives his just desserts by being scratched all over by the thorns of the prickly wild brinjal plant – the victory of intelligence over guile. And so herein ends my story, albeit with much respect for the ‘begoon’ and what seems like a wonder plant that India gave the world.