Why do the Bengalis revel in an irreverent food orgy during Durga Puja even as the rest of India celebrates the goddess for nine days with a pure vegetarianism that omits even grains and flours from daily meals? This is something many are curious about, but are afraid to ask. The reasons, if you dig deep, are anything but irreverent; they are a vestige of a primitive, even pre-historic, folk religion that continues to flow through Bengal’s veins. The Mother Goddess, like in all ancient civilisations, was born of the earth, out of a respect to nature’s bounty on the one hand and a fear of the destruction of all that supported life on the other. Depicted in the Puranas and the epics as a female warrior, the annihilator of Asuras, or all that was evil, scholars point to this as having partly a historical basis representing the conflict between the Indo-Aryans and ethnic tribes.

Durga was originally the Mother Goddess, the annihilator of asuras. Photo courtesy: Pixabay

Matriarchy and a mountain deity

A curious fact pointed out by a friend recently is that Durga Puja greetings are never Shubho Pujo (Auspicious Pujo) – it is always Sharad Shubhechha (Autumn or autumnal greetings). Moved from the earlier spring festival called Basanti puja to autumn by Lord Ram’s untimely invocation of the goddess, this at once makes it apparent that the celebration was seasonal and about all the new beginnings it heralded with plentiful food and drink. This is still apparent in the Nabapatrika (leaves of nine plants), an important part of Durga Puja, without whose invocation the puja rituals cannot commence. In times when idol worship was not common, tribal communities worshipped Goddess Nabapatrika in autumn, and prayed for a bountiful harvest. The nine plants – banana, colocasia, turmeric, jayanti, wood apple, pomegranate, ashoka, arum and paddy – were as much an ode to nature as representatives of nine folk deities.

A food stall near a pandal in Bangalore. The Travelling Slacker/Flickr

Invoked in times of trouble, Durga etymologically means one who is approached with difficulties. She emerged from a primitive form of a mountain war deity —Chandica or Durga — who was fond of liquor and sacrificial meats, and worshipped by matriarchal tribal communities in the Himalayas, and the Vindhyas, and hence, also referred to as Vindhyavasini. Along with Tara from Tantric Mahayana Buddhism, Chandica was firmly established in India by the 2nd century AD. It would take another ten centuries for organised Hinduism to make permanent inroads into Bengal .

The politics of redefining the Goddess

With the march of civilisation and monotheism, says scholar Shiv Kumar Tiwari, the warrior folk goddess along with divinities, was transformed into the personification of the all-destroying time (Kali), the primordial energy (Adya Shakti), and the deliverer from Samsara (the cycle of rebirths). In due course, she was gradually aligned with the Brahminical Hindu discourse on mythology and philosophy.

As patriarchy gained ground, the goddess was recreated as Durga, Mahisasura Mardini or Shakti, born of attributes gifted by the male gods; as Uma or Gauri, the daughter of the Himalayas; as Parbati or Sati, the wife of Shiva; as Mahamaya or Annapurna, exuding femininity and pure maternal instincts with four children. Sounds familiar?

Ancient Indian discourse describes food as prana, i.e., life, as food sustains life, and provides nutrition. Food traditions within the same culture vary according to region, family and gender. Likewise, worship of the goddess in her varied forms was observed privately in homes, each following a different tradition. With the patriarchal system now firmly in place, women were entrusted with organising the rituals while the men performed and partook of them. Deprived of their earlier status in a matriarchal society, the women fell back on age-old, accepted folk rituals.

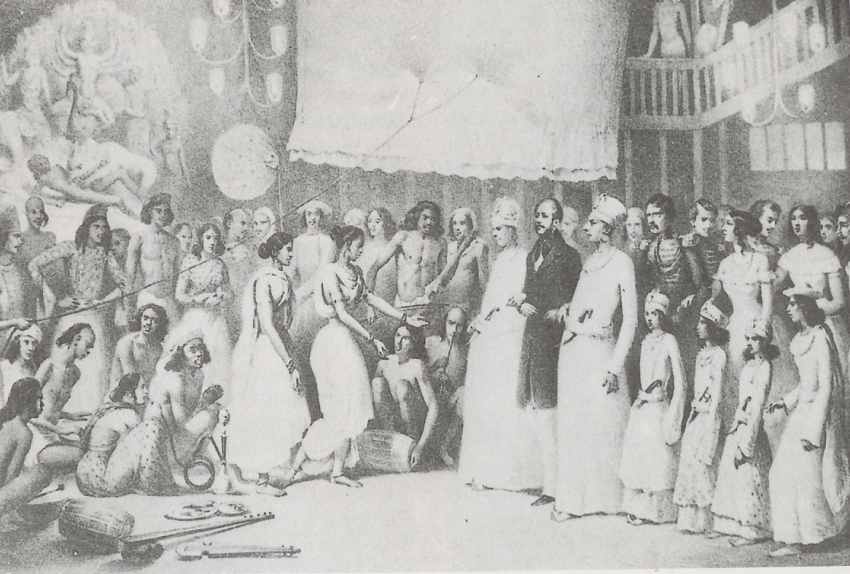

A Raj-era painting of Durga Puja celebrations in Shobhabazar, in Kolkata. Wikimedia Commons

A Raj-era painting of Durga Puja celebrations in Shobhabazar, in Kolkata. Wikimedia Commons

How gender defined the celebratory food

Women were deemed best in the kitchen and the food they cooked was impacted by the bounty of the region; their position in the household as a single, married, or widowed individual, which meant they ate whatever was leftover; and last but not the least their own desires, much of which was denied them. Gone was the tribal equity of unfettered eating. Meat did not figure in the women’s diet, and fish, therefore, held great significance in a married woman’s life, signifying her husband’s long life. No one would allow a ‘married woman’ to leave the house without offering her fish and rice.

The goddesses, too, were assigned their designated foods. For Durga it was pantaa bhaat (fermented rice) and kochur shaak (colocassia stalks). Kali demanded parboiled rice and lesser fish such as boal, magur, shol and greens such as colocassia and bottle gourd cooked with fish head, given her tamasik nature. It was plain greens and rice for Annapurna, the eternal mother who made do with whatever was at hand; and hilsa and koi for Laxmi, signifying expensive fish reserved for married, well-to-do ladies. These are some of the foods we see being served ritually at traditional family puja bhogs.

Gradually, as a result of various religious movements in eastern India, the ritualistic worship of the Devi got split up into three ritualistic schools. The Shakta tradition, the first to take root, worships Durga as Shakti, the Divine Energy, as Dasabhuja with 10 arms, Jagaddhatri, the eternal mother, Annapurna, the goddess of fertility, the destroyer Kali, Uma or Gauri, Sati or Parvati and so on. Therefore, the cuisine, too, evolved to its varied best, symbolising thanksgiving for plenty. Needless to say, since the Bengali Brahmin had received the sanction to be non-vegetarian by the scriptures, fish was in abundance as was sacrificial meat, albeit sans onion and garlic, in commemoration of the Devi’s victory over evil. The Vaishnava tradition upholds non-violence and hence, the tradition of pure vegetarian food sans onion and garlic – the widow’s refuge. This is also the cuisine preferred at the community pujas and temples, referred to as bhog, in order to be inclusive. The third tradition, Tantric, remains entrenched in more primeval times, in which Durga is worshipped as Kali (the Dark Goddess), or Chamunda, and is also associated with black magic. Wine and meat, therefore, form the major part of this school’s ritualistic food.

The community bhog is influenced by Vaishnavite school of thought,

which upholds non-violence. Kushal Ghosh/Flickr

Return of the prodigal daughter

As the bloodthirsty aspects of the goddess began to mellow with her diminished status in a patriarchal set up, Durga’s identity in Bengal metamorphosed to that of a daughter returning to her maternal home with her children for a short five-day vacation. So, like all parents, the families celebrating the festival fed her the best of multi-course gourmet fare, according to the schools of worship they followed. And, of course, since she was a married woman, fish had to be, according to Shakta or Tantric rituals, an intrinsic part and meat the high point of the celebrations.

This diversity of ritual eating found common ground when the puja stepped out of family homes into the neighbourhoods as a community festival. There was something for everybody, no matter which religious tradition they followed. There was no writ saying that one could partake of this, but not that. It was a personal choice. After having fasted until the completion of the main puja ritual and partaking of the prasad offered to the goddess, the community then explodes into an orgy of celebratory feasting. The party begins, because Uma is home.

Featured image: Sunetro Lahiri/Flickr