While reading some of socio-cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai’s essays, I came across a rather interesting thought. He says: “Cookbooks, which usually belong to the humble literature of complex civilisations, tell unusual cultural tales.” Through the past decade or so, there has been an explosion of cookbooks and food related writings in India, both in the English language and vernacular, in print as well as in the virtual world. Was food always such an integral part of our social lifestyle, something to be celebrated instead of just being a necessity?

If we look beyond Indian shores, the first printed cookbooks had made an appearance in the public sphere in Europe by the mid-15th century. So what is the story of the cookbook in India? Who were they written for? What were the kind of recipes they first started out with?

From holistic living to haute cuisine

Food has always formed an important part of Indian discourse from ancient times. However, much of it had to do with high thinking, the principles of medicine and holistic living rather than culinary sophistry. Fast forward to medieval India, and we see the transformation beginning. It was the Mughal kitchen that changed the very way that the average Indian thought about food. Gastronomy was given the status of an art form and elaborated upon in the beautifully calligraphed annals of emperors Babur, Akbar, Jehangir and Shah Jehan.

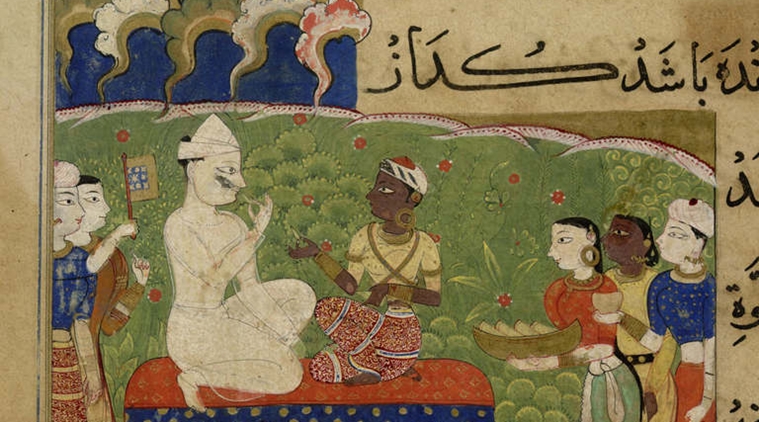

The Nimatnama, among the most famous books dealing with food in medieval India, contains, among others, recipes for Flavoured Mutton, Samosas, Vadas and many other dishes. Wikimedia Commons

Down South, Manasollasa, the oldest surviving tome dealing with cookery, is from the 12th century, and was compiled under the patronage of Chalukya king Someswara III. Of encyclopaedic proportions, Manasollasa’s 268 verses on food provide a wide range of vegetarian and non-vegetarian recipes with separate sections on the enjoyment of food and drink, touching also upon the presentation and visual aesthetics of food.

It is from these records of social history that we also get important nuggets of information about eating habits and styles. It is stressed that a King had to eat on a silver plate with bowls made of gold. Or, for instance, however shocking it may sound, it is from ancient texts like the Sangam literature of present day Tamil Nadu that we learn that elephant meat was popular or that fish scrotum was a delicacy, as outlined in Manasollasa, with a full recipe that directed one to take out the scrotum of fish and roast them in fire, when hardened cut into pieces and fry in smoking oil and then season with powdered cardamom, pepper, rock salt and asafoetida.

In the eastern region that is in Bengal, 13th century folk literature known as the Mangalkavyas sang paeans to the food cooked by the women of the times. Through food we get us our first glimpse of the social differences that existed, and the distinctiveness of the cuisines of the western and eastern parts of Bengal. Nidaya, the wife of a hunter-gatherer, cooks with various water-body greens and wild rabbit meat from the forests, with yoghurt as dessert. Whereas Lahana and Khullana, the two wives of a rich merchant, stir up a storm with various fish and meats, cooked in ghee and rounded off with rice pudding and elaborate sweetmeats. Here we learn that chopped sheepskin and wild boar were popular items in community feasts. It is clear then that the first wave of the Indian gastronomic revolution had started. Suddenly food became the benchmark of affluence and households aspired to host tables at their lavish best.

The medieval gave way to the modern with the advent of the Europeans. Even while new influences were embraced wholeheartedly, the princely states of India, in emulation of the Mughals and in order to hold on to their royal lineage, began recording their closely-held family recipes in handwritten manuscripts. I was lucky to chance upon one, shared with me rather generously by the Delhi-based food historian and culinary expert Ashish Chopra. Gifted to him by the Diggi royal family, more than 350 recipes for various dals, vegetables, meats, pickles, local brews and coolers are written in clear and legible script in the Marwari language, some dutifully assigning credit to other royal families from whom they were collected. Contrary to our stereotyping of vegetarian food, I was pleasantly taken aback to discover a recipe for Mans ki Dhokla or meat dhokla. We can then safely presume that the first cookbooks, albeit for private circulation, were written by aristocratic households. And so was born ‘haute cuisine’ or high cuisine. And like haute cuisine all over the world it sought to distance itself from the common man’s food.

Hot off the press to the commoner’s table

This second culinary wave and the one that had a huge impact on the tradition of recipes handed down from mother to daughter was fuelled by the arrival of the printing press in India. Brought by Christian missionaries, the first rush was obviously to print bibles but it soon became the agent of a huge socio-political change that swept through India. Bengal became a pioneer, churning out books in various disciplines in 40 languages by the early 19th century.

Therefore it is not surprising that some of the first cookbooks to be printed in India came out of the Bengal stable. Here, I am not talking about cookbooks published by the colonial rulers in the English language but the first ones printed in the vernacular. Those that emerged from their elite private domains and reached out to the masses. Even then the first of them came out of the portals of the rich and famous. For the simple reason, as Appadurai explains, they were the ones who could afford complex cuisines.

The arrival of the printing press fuelled a second culinary wave, and some of the first cookbooks

to be printed in India came out of Bengal. Photograph via wmcarey.edu

One such book was Pak-Rajeswar, roughly translated meaning the Emperor of Cooking, published by His Highness Mehtab Chand of the princely state of Burdwan in 1831. He followed it up with another called Byanjon-Ratnakar (Fashioning Gems out of Victuals). Ostensibly in Bengali, it is, however, a far cry from what we know as Bengali today. Compiled by a Brahmin pandit assigned to do the task for the Maharaja, it is essentially in the language of the elite, bordering on Sanskrit, befitting a royal court.

Both these books hark back to Appadurai’s observation that cookbooks tell unusual cultural tales. A book out of Bengal in Bengali must be about shukto and fish curries and malaikari? Of alu posto and phulkopir dalna? Wrong. It showcased processes and recipes from three sources – the first was techniques and culinary principles of ancient India, the second from the culinary traditions of the Mughal emperor Shah Jehan and the last but not the least, the personal favourites of the Maharaja of Burdwan – a mix of Mughlai and frontier food. Meat dishes occupy a major part of the book with just a couple of fish recipes in the genre of kebabs and pulaos. Not surprising since the family originally hailed from Lahore and carried the family name of Kapoor.

While meat may have dominated the pages of the above cookbooks, it also gives us an important insight into the regional culinary practices of the times, especially with regard to Hindus. Meat recipes in the Pak-Rajeswar and Byanjon Ratnakar have little mention of onion and garlic, otherwise heavily used in Mughlai cuisine. The author of Pak-Rajeswar explains that onion had not been listed as an essential ingredient in the execution of these recipes because people in the region hardly consumed it. It can then be safely assumed that even till the mid-19th century, onion and garlic had not formally entered the Bengali Hindu kitchen and their unabashed use is barely a 150-years old. This is borne out by the fact that another cookbook Pakprabandha (Kitchen Prose) published in 1879 written by an anonymous Bengali woman, for the first time mentions the use of onion and garlic.

Meat recipes in the Pak-Rajeshwar contain little mention of onion and garlic, which are

otherwise heavily used in Mughlai cuisine. Even until the mid-19th century, onion and garlic

had not entered the Bengali Hindu kitchen. Wikimedia Commons

To get back to the Burdwan cook books, it is interesting to note that there is no mention of the potato, cauliflower, cabbage or tomato, an integral part of Indian cuisine today. That is because they had still not entered the Bengali culinary lexicon. Cauliflower was introduced to Indian agriculture around 1850, cabbage just a little earlier. Tomatoes arrived in India around 1880 and while by 1830 the potato was being cultivated aggressively in Dehradun and had reached the Calcutta markets, it obviously had not still caught the imagination of Bengal.

Levelling the culinary playing field

Illustration by Suvarna Patil Silgardo

Mehtab Chand was known as a man of letters, with the distinction of introducing a new kind of Bengali script. So why would such a man publish cookbooks instead of scholarly works? The times were changing fast and aspirational levels were rising. Everyone strove to be at par with the lifestyle of the colonial masters. They wanted to be dress like them, speak like them, eat like them and entertain like them. The magazines and newspapers of the late 19th century had begun reflecting that change by way of articles that urged young housewives to learn new ways of cooking and about new foods in order to be in step with modern times.

It was also emphasized that delectable foods were a way of keeping the husband firmly by the woman’s side. So some of the recipes listed aphrodisiacal qualities, subtly urging the women to aid their men’s virility. For instance, the recipe for a sweetmeat called Sohan Mohan Bhog in the Byanjon Ratnakar has a footnote saying: “If 125gm of this Mohan Bhog is had every night, it will increase strength, sperm count and sexual vigour.” These two books therefore were pathbreaking publications heralding a new era in the appreciation of food in the Indian culinary landscape. Their popularity can be gauged from the fact that in those times, between 1831 and 1881, Pak-Rajeswar ran into three editions.

The rest is history. The printing press broke social inhibitions and gender biases. Cookbooks written by women authors came in quick succession ranging from those by educated middle-class housewives to royalty like Maharani Gayatri Devi. What we are experiencing today is the third wave of India’s discovery of its gastronomic legacy. Today it’s a level playing field with the Maharaja vying for space amidst the commoners’ sudden discovery of the treasure trove of regional culinary jewels that are hidden in every Indian home. The wheel has come full circle, from elaborate ‘high’ cuisine back to the ‘low’ and simple, pure flavours that had once marked our food. And the rush is on to record every recipe, every nuance and every tradition that once existed and still does.